Let the legacy of Pak Ungku be the benchmark

Emeritus Professor Tan Sri Dato' Dzulkifli Abdul Razak

Opinion - New Straits Times

December 18, 2020

DEC 15 will be one of the darkest days for Malaysian education. An intellectual giant has just left the scene after the longest time colouring the scenes as a young academic as well as the Vice-Chancellor helming the country's oldest university.

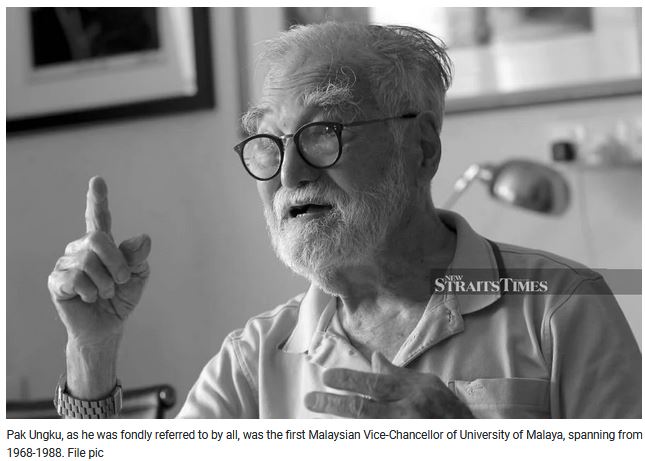

Pak Ungku, as he was fondly referred to by all, was the first Malaysian Vice-Chancellor of University of Malaya, spanning from 1968-1988, taking over from the last British counterpart.

When I entered the academic world then, his aura had already created a long-lasting impact on academia. Indeed, as a student in the early 1970s, Pak Ungku had earned much respect from the student population. He was a man of principle worthy of his stature. Let alone as Vice-Chancellor of a premier university.

So it is no surprise that Pak Ungku led the list of names of the then vice-chancellors who pioneered a handful of local universities. They include the late Rashdan Baba, Ainuddin Wahid and Hamzah Sendut. Pak Ungku, at 98, was the last of the Mohicans as it were. Each of these names remains in the minds of many, not just the university community – staff and students, but also the public at large.

They themselves were committed public intellectuals who were grounded in the community around them, and often acted as custodians for their well-being and interest. Pak Ungku's exemplary social commitment on the socio-economic front for the rakyat is particularly notable, epitomised by the establishment of the unique Tabung Haji and Angkasa, the national cooperative; to name but a few.

These legacies live on until today, as proof of how relevant his ideas were to impact the people in real-life. They were not empty academic gimmicks that were often launched to capture mere short-lived sensation and nothing more.

As such, University of Malaya became well known without the need to be ranked, or for league tables or KPIs. Indeed, they were unheard of, unlike today, where they are embraced obsessively by most. All the universities then were "unnumbered" but not unknown globally. On the contrary, they were highly sought after without much "marketing" as the tendency is nowadays. They were well recognised because the academic leadership and governance mirrored what were globally expected of them and the institutions.

I recall Pak Ungku declaring that he would not lead an institution that is not autonomous. Period. With such clarity it is no wonder that he stood tall and well respected by his peers and detractors alike. Interestingly enough, his ascent to the highest office at the university came at a time when the University Council then was chaired by a staunch leader of an opposition political party.

Yet, Pak Ungku remained unwavering as an academic leader par excellence, serving longer than any of the vice-chancellors or the equivalents (president, CEOs, etc) – public or private, serving after him. In short, the university, as sanctity of knowledge, was well guarded from interference from the powers that be. A departure from what is currently being practiced.

Unfortunately, things took a different turn after Pak Ungku left office. The evidence for this is apparent as universities gradually became "politicised." Slowly but surely, the education landscape, especially at the tertiary level, got eroded of its autonomy and become more bureaucratised.

Over time, the functions of the universities were compromised as the sanctum of knowledge. Absorbed into the bureaucracy, and swayed by the politics of the day, universities were generally reduced to the level of government departments.

The mantra "those who pay the piper call the tune" drove the last nail in the university's coffin as an autonomous institution. The academic leadership is blurred in the mist as observed today. The likes of Pak Ungku and his contemporaries are gone perhaps forever. Today, chances are we will be hard pressed to name the kind of leaders at any of the local universities – either public or private.

Perhaps, all is not lost, as recounted by many with fondness (on the day of his departure) on how Pak Ungku played his role as an academic leader and public intellectual. How this giant in our educational landscape dwarfed the line-up of so-called "academic" leaders after him is mind-boggling.

Despite the many processes introduced of late, ranging from profiling to ranking, there is yet to be anyone coming close to Pak Ungku! Though more than 30 years have lapsed since he left office, no one comes close to Pak Ungku. What is more, when he is no longer with us, with only his legacy to remind us. That too will soon slip away if nothing concrete is done to root them back into the academic institutions nationwide.

One way to do this is to let his legacy be the national benchmark on how to bring back the true meaning of academic leadership, starting from the vice-chancellor right down to the young academics and administrators. The emphasis must be on how to serve not just universities but also engaging the community at large, and what to make out of the knowledge generated for the betterment of the little people on the street. And how to translate the outdated ivory tower image to a beacon for humanity.

This is not only imperative as we struggle to reshape the education post-pandemic, but more importantly, to live the values that Pak Ungku had espoused through his impressive career, if not lifetime. And to recognise them as the way forward will differentiate the authentic from the ones who are merely rhetorical, if not hypocritical.

It is entirely up to us and our worthiness as academic leaders to make up our minds for the sake of the future generation in the face of an uncertain time ahead. Pak Ungku, rest in peace. You will be sorely missed.

The writer, a 'New Straits Times' columnist for more than 20 years, is International Islamic University Malaysia rector