Interlocking with the past

Professor Tan Sri Dato' Dzulkifli Abd Razak

Comment

New Sunday Times - 01/16/2011

THE last time we heard about a book burning threat was by a pastor of a little known church in Florida, the United States last year.

The threat fizzled out despite the publicity.

Last week, we read of a similar episode on the home front when books were actually burnt!

Book burning frenzy has a long and interesting history, dating back to the early century BC during the Qin Dynasty.

The idea then was to make books inaccessible, at times as a policy out of hatred such as in the case of the Nazi regime.

At other times, even seemingly innocuous novels such as the Harry Porter series also got burnt by some disgruntled group.

Burning books is anti-intellectual as we progress towards becoming a knowledge society.

Among book lovers, even the most hated publication is a valuable source of reference.

It can serve as an important information to rebut what is regarded as "offensive" and enlighten those who care about an issue and want to know more about it.

Moreover, unlike previously, regardless of how many books are burnt or destroyed, chances are there will still be copies available online.

An example is recent failed attempts by some of the most powerful governments and corporations worldwide to suppress WikiLeaks as a source of information.

In fact, the converse happens, with many more mirror sites being set up, attracting others to visit them out of curiosity.

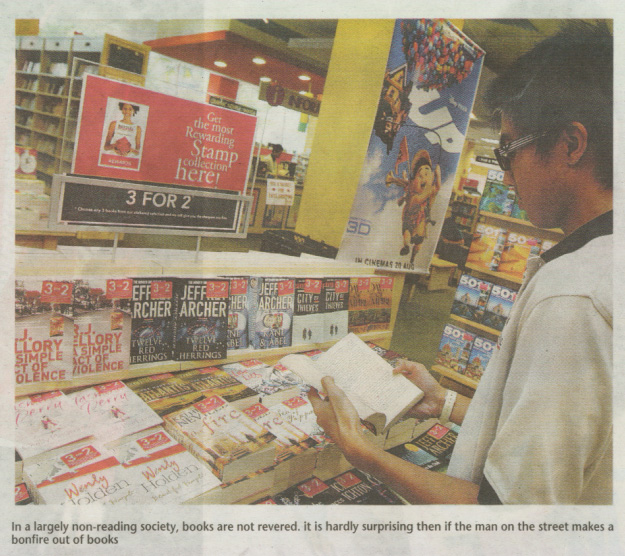

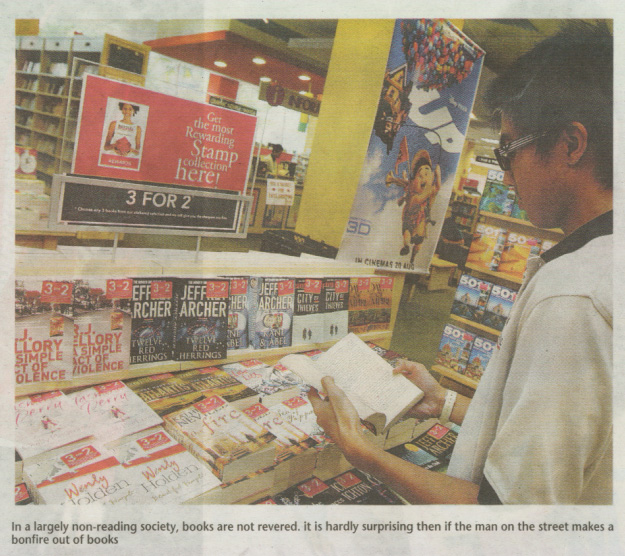

In a largely non-reading society like ours, books are not as revered.

Even in libraries in universities, pages get torn or mutilated because one disagrees with what have been written.

It is hardly surprising then if the man on the street makes a bonfire out of books.

The question is whether these books have been thoroughly read and their message fully understood within the proper context before they were burnt.

This is the crux of the matter. Words, phrases and sentences -- in fact the storyline -- can give different meanings within a contrasting context.

"Benign" words can sound offensive if the context differs.

This problem is compounded by different languages.

Consider similar sounding words in Bahasa Malaysia and Bahasa Indonesia despite the intimate cultural proximity of each country.

Each word has different meanings (at times vulgar) if taken literally, and the cultural context of the message ignored.

While budak is a child in Bahasa Malaysia, it means slave in Bahasa Indonesia.

Does it mean that all books or novels with those perceived "offensive" words be banned, or worse, destroyed in both nations?

More broadly, take the word "nigger" which is offensive when used in place of "native Africans".

Yet, in Roots by Alex Haley, it is used many times to depict the situation of the time when Haley's ancestor Kunta Kinte was forced into slavery. The word "nigger" is the reality of history in a context of how the toubob (or whites -- another controversial word) justified the enslavement of Africans, allegedly given "their African pasts of living in the jungles with animals gave them a natural inheritance of stupidity, laziness, and unclean habits" (page 353).

Even in the days of apartheid in South Africa, such words were freely used and recorded in the annals of history, narratives and novels. They remain there as a matter of historical fact.

To remove such a word would be tantamount to manipulating history because the context will be forever and totally lost, and history "whitewashed".

By doing so we unwittingly "sanitise" the injustices of the toubob.

This is not only wrong but also a crime it in itself!

It is for this reason that we must make History compulsory so that the context of the events are properly understood, and not misunderstood out of ignorance or arrogance.

Otherwise, it will be just like the ignoramus who will unjustifiably hammer down all things that stick out given the narrowness of his knowledge.

Similarly, someone with a coloured political outlook tends to politicise everything through his myopic lens in viewing the wider world.

The German writer Herman Heine said: "Where they burn books, so too will they in the end burn human beings" (in reference to the burning of the Quran during the Spanish Inquisition).

In short, to interlock with the past, we must first unlock our minds and remove our blinkers.

* The writer is the Vice-Chancellor of Universiti Sains Malaysia. He can be contacted at vc@usm.my

Comment

New Sunday Times - 01/16/2011

THE last time we heard about a book burning threat was by a pastor of a little known church in Florida, the United States last year.

The threat fizzled out despite the publicity.

Last week, we read of a similar episode on the home front when books were actually burnt!

Book burning frenzy has a long and interesting history, dating back to the early century BC during the Qin Dynasty.

The idea then was to make books inaccessible, at times as a policy out of hatred such as in the case of the Nazi regime.

At other times, even seemingly innocuous novels such as the Harry Porter series also got burnt by some disgruntled group.

Burning books is anti-intellectual as we progress towards becoming a knowledge society.

Among book lovers, even the most hated publication is a valuable source of reference.

It can serve as an important information to rebut what is regarded as "offensive" and enlighten those who care about an issue and want to know more about it.

Moreover, unlike previously, regardless of how many books are burnt or destroyed, chances are there will still be copies available online.

An example is recent failed attempts by some of the most powerful governments and corporations worldwide to suppress WikiLeaks as a source of information.

In fact, the converse happens, with many more mirror sites being set up, attracting others to visit them out of curiosity.

In a largely non-reading society like ours, books are not as revered.

Even in libraries in universities, pages get torn or mutilated because one disagrees with what have been written.

It is hardly surprising then if the man on the street makes a bonfire out of books.

The question is whether these books have been thoroughly read and their message fully understood within the proper context before they were burnt.

This is the crux of the matter. Words, phrases and sentences -- in fact the storyline -- can give different meanings within a contrasting context.

"Benign" words can sound offensive if the context differs.

This problem is compounded by different languages.

Consider similar sounding words in Bahasa Malaysia and Bahasa Indonesia despite the intimate cultural proximity of each country.

Each word has different meanings (at times vulgar) if taken literally, and the cultural context of the message ignored.

While budak is a child in Bahasa Malaysia, it means slave in Bahasa Indonesia.

Does it mean that all books or novels with those perceived "offensive" words be banned, or worse, destroyed in both nations?

More broadly, take the word "nigger" which is offensive when used in place of "native Africans".

Yet, in Roots by Alex Haley, it is used many times to depict the situation of the time when Haley's ancestor Kunta Kinte was forced into slavery. The word "nigger" is the reality of history in a context of how the toubob (or whites -- another controversial word) justified the enslavement of Africans, allegedly given "their African pasts of living in the jungles with animals gave them a natural inheritance of stupidity, laziness, and unclean habits" (page 353).

Even in the days of apartheid in South Africa, such words were freely used and recorded in the annals of history, narratives and novels. They remain there as a matter of historical fact.

To remove such a word would be tantamount to manipulating history because the context will be forever and totally lost, and history "whitewashed".

By doing so we unwittingly "sanitise" the injustices of the toubob.

This is not only wrong but also a crime it in itself!

It is for this reason that we must make History compulsory so that the context of the events are properly understood, and not misunderstood out of ignorance or arrogance.

Otherwise, it will be just like the ignoramus who will unjustifiably hammer down all things that stick out given the narrowness of his knowledge.

Similarly, someone with a coloured political outlook tends to politicise everything through his myopic lens in viewing the wider world.

The German writer Herman Heine said: "Where they burn books, so too will they in the end burn human beings" (in reference to the burning of the Quran during the Spanish Inquisition).

In short, to interlock with the past, we must first unlock our minds and remove our blinkers.

* The writer is the Vice-Chancellor of Universiti Sains Malaysia. He can be contacted at vc@usm.my