In the tradition of Andalusia

Professor Tan Sri Dato' Dzulkifli Abd Razak

Learning Curve : Perspective

New Sunday Times - 02/27/2011

AN exhibition of 16 monumental sculptures, which pays tribute to the Nasrid architecture of the notable Alhambra Palace, will be displayed at Madrid’s Reitro Park and Plaza de la Independencia in Spain until the end of April.

The display of the sculptures by famous artist Cristóbal Gabarrón is in conjunction with the 15th anniversary of Cristóbal Gabarrón Foundation.

Learning Curve : Perspective

New Sunday Times - 02/27/2011

AN exhibition of 16 monumental sculptures, which pays tribute to the Nasrid architecture of the notable Alhambra Palace, will be displayed at Madrid’s Reitro Park and Plaza de la Independencia in Spain until the end of April.

The display of the sculptures by famous artist Cristóbal Gabarrón is in conjunction with the 15th anniversary of Cristóbal Gabarrón Foundation.

The artist’s colourful and contemporary Towers of Alhambra highlighted the multicultural nature of a society where Muslims, Jews and Christians lived harmoniously together.

The forms and graphic elements, and even construction, are said to reflect the monument’s multicultural nature.

According to the artist: “Every one of the sculptures represents one of the towers of the Alhambra, but it represents not the Alhambra itself but the spirit of all the years and all the centuries it embodies, the spirit of dialogue and respect among cultures.”

To internalise this spirit of dialogue and respect among cultures, there can be no other way except to be subliminally engulfed by the architectural paradise itself.

One brochure aptly claims: “If you have not seen the Alhambra, you have not seen anything yet.”

To which I add: “And you have not begin to feel the spirit of beauty and finesse as well as care it exudes over the centuries.”

This is in light of our so-called dialogues among cultures, which lack the beauty, finesse and care that the Alhambra seems to insist on, and the current debunking of multiculturalism in Europe.

Ever so striking is the inscription Wa la ghalib illa Allah (There is no victor but the One God) that adorns this glorious monument.

It stands out almost like a “tagline” of the Alhambra, as an institution with a global presence and mission as it were, in today’s terms.

It was recorded in one official narration that this majestic structure “conveyed to us the message of faith in the Unity of a world wherein the invisible can be deciphered only through the ‘signs’ of the visible, without ever becoming reduced to them”.

Yet today, we are so enthralled by the reductionist world of the visible that is devoid of the intangibles, other than what we can crudely quantify as “excellence” — one which is “without soul” (consciousness) as some are beginning to point out of late.

Akin to a living form, water is present throughout the entire layout of the Alhambra, like a circulatory system interconnecting one part of the human body to the next, refreshing and enriching it.

Water is an integral way of life, crucial to daily cleansing and ablutions, from birth to death.

With fountains gushing from the Court of the Lions (Patio de los Leones), which stands out starkly, to the more subtle ponds among the many quadrangles and lush gardens, and the discreetly hidden hamam or bath, the Alhambra breathe life at all times.

Some even liken the ever flowing water to the river images of paradise that many scriptures and holy books allude to.

Once again, it is the visible connecting to the invisible; the here-and-now to eternity.

While water is fast becoming a wasted resource, given the state of affairs today, it is not so in the days of the Alhambra.

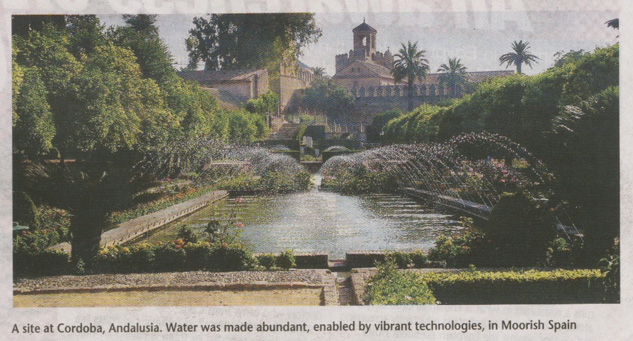

Water was made abundant not just in the palace, but throughout life in Andalusia, enabled by the vibrant Andalusian technologies, such as the waterwheel, watermill, dam, vent, lock and underground drainage that make water more readily available.

They nourished land into fertile oases and orchards through sophisticated systems of aqueducts and irrigation, so much so Italian engineer Juanello Turriano reportedly visited Andalusia in the 11th century to learn about them.

Without doubt, Andalusia is truly the birthplace of the first European Renaissance that started in 13th century Moorish Spain.

In a nutshell, the Alhambra is in itself a never-ending dialogue of values and respect for life, not just for daily sustenance but for a much longer period of existence, at its different stages and forms.

It stood for a universal message that is easily understood by those who seek more than what life has to offer in the temporal sense, namely, that all victories belong to God alone.

Ibn Zamrak (1333-1393), the most famous poet of Alhambra, dialogued this in his poem (qasida) about the fountains of the Court of the Lions, in an excerpt, saying: “Don’t you see how water overflows the borders, and the warned drains are here against it?

“They are like the lover who in vain, tries to hide his tears from his beloved...”

The forms and graphic elements, and even construction, are said to reflect the monument’s multicultural nature.

According to the artist: “Every one of the sculptures represents one of the towers of the Alhambra, but it represents not the Alhambra itself but the spirit of all the years and all the centuries it embodies, the spirit of dialogue and respect among cultures.”

To internalise this spirit of dialogue and respect among cultures, there can be no other way except to be subliminally engulfed by the architectural paradise itself.

One brochure aptly claims: “If you have not seen the Alhambra, you have not seen anything yet.”

To which I add: “And you have not begin to feel the spirit of beauty and finesse as well as care it exudes over the centuries.”

This is in light of our so-called dialogues among cultures, which lack the beauty, finesse and care that the Alhambra seems to insist on, and the current debunking of multiculturalism in Europe.

Ever so striking is the inscription Wa la ghalib illa Allah (There is no victor but the One God) that adorns this glorious monument.

It stands out almost like a “tagline” of the Alhambra, as an institution with a global presence and mission as it were, in today’s terms.

It was recorded in one official narration that this majestic structure “conveyed to us the message of faith in the Unity of a world wherein the invisible can be deciphered only through the ‘signs’ of the visible, without ever becoming reduced to them”.

Yet today, we are so enthralled by the reductionist world of the visible that is devoid of the intangibles, other than what we can crudely quantify as “excellence” — one which is “without soul” (consciousness) as some are beginning to point out of late.

Akin to a living form, water is present throughout the entire layout of the Alhambra, like a circulatory system interconnecting one part of the human body to the next, refreshing and enriching it.

Water is an integral way of life, crucial to daily cleansing and ablutions, from birth to death.

With fountains gushing from the Court of the Lions (Patio de los Leones), which stands out starkly, to the more subtle ponds among the many quadrangles and lush gardens, and the discreetly hidden hamam or bath, the Alhambra breathe life at all times.

Some even liken the ever flowing water to the river images of paradise that many scriptures and holy books allude to.

Once again, it is the visible connecting to the invisible; the here-and-now to eternity.

While water is fast becoming a wasted resource, given the state of affairs today, it is not so in the days of the Alhambra.

Water was made abundant not just in the palace, but throughout life in Andalusia, enabled by the vibrant Andalusian technologies, such as the waterwheel, watermill, dam, vent, lock and underground drainage that make water more readily available.

They nourished land into fertile oases and orchards through sophisticated systems of aqueducts and irrigation, so much so Italian engineer Juanello Turriano reportedly visited Andalusia in the 11th century to learn about them.

Without doubt, Andalusia is truly the birthplace of the first European Renaissance that started in 13th century Moorish Spain.

In a nutshell, the Alhambra is in itself a never-ending dialogue of values and respect for life, not just for daily sustenance but for a much longer period of existence, at its different stages and forms.

It stood for a universal message that is easily understood by those who seek more than what life has to offer in the temporal sense, namely, that all victories belong to God alone.

Ibn Zamrak (1333-1393), the most famous poet of Alhambra, dialogued this in his poem (qasida) about the fountains of the Court of the Lions, in an excerpt, saying: “Don’t you see how water overflows the borders, and the warned drains are here against it?

“They are like the lover who in vain, tries to hide his tears from his beloved...”

The dialogue continues with Gabarrón’s crowning tribute to the Alhambra in the Andalusian tradition gone by.

* The writer is the Vice-Chancellor of Universiti Sains Malaysia. He can be contacted at vc@usm.my