Making sense of going global

Professor Tan Sri Dato' Dzulkifli Abd Razak

Learning Curve : Perspective

New Sunday Times - 02/07/2010

It is almost a cliché that higher education today must be internationalised if it were to be deemed as credible.

In fact, most institutions claim that they are internationalised, with permanent positions created to ensure that this actually happens.

Otherwise, they would be forced to do so by league table promoters who assign high points to such activities.

That is why we hear that some are hiring foreign faculty members to meet this aspiration because “internationalisation” often implies diversity of nationalities.

Even though there is a large number of local academics trained in diverse top-notched international environment and cultures, this is considered insufficient.

It is not surprising that meager resources are being channelled to meet such flimsy criteria, often at the expense of other priorities.

Some institutions claim to be the world’s most international institutes of higher learning (HEIs) or a global university to attract students. Never mind the quality of education, or whether it is truly international.

What is most puzzling is that these self-proclaimed HEIs are among the most well-advertised institutions, often supported by personalities less known in the academic world.

One would expect such institutions to be on every potential student’s lips and that the money spent on such promotional materials be put to better use.

It appears that being international comes at a price — assuming that this amount (and more) will be recovered through the number of students gullible enough to believe the assortment of fancy advertisements.

At one international meeting, I recall being asked if the Pacific International University in Malaysia is as good as it claims to be. Such is the power of advertisement, and until now I am still on the lookout for such an outfit in Malaysia!

But these are nothing new as universities increasingly behave like factories for the much sought after human capital. One of the tests for internationalisation had presented itself in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake on Jan 12.

Even before the tragedy, no university — no matter how international — had dreamed of setting up a branch campus, for example, on the beleaguered island. This is despite the fact that it is in the Western Hemisphere where most of the top international universities are located.

Not that the Haitians have no use for world-class international universities but rather the universities tertiary institutions have no use for the Haitians in the overall scheme of things. Instead, all are rushing to selected Asian countries — again sidelining the ones within Haiti’s league.

So much for internationalisation of higher education, which is beginning to sound more and more like commercialism.

Worst of all, we have yet to hear any big announcement of educational support — perhaps something similar to the Colombo Plan — from the rich and famous world-class universities!

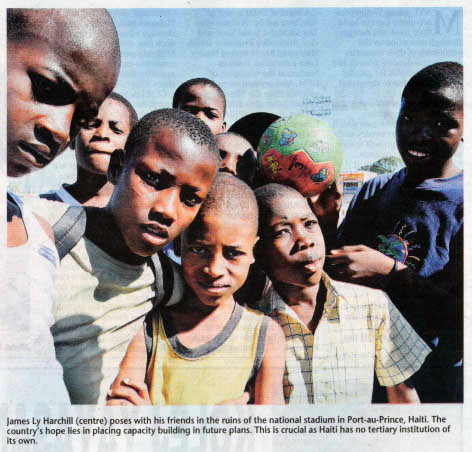

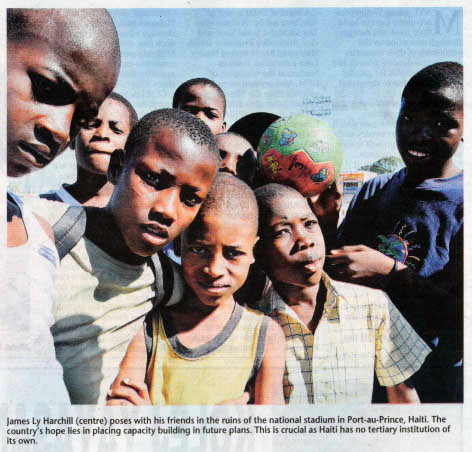

Haiti’s hope to break free from its past lies in placing capacity building in any future plan to develop the island. This is crucial as Haiti has no tertiary institution of its own.

Could this be an opportunity for the likes of the Pacific International University to grab? We will just have to wait and see.

Even as the term “internationalisation” gains popularity, a firm meaning (of the word) has yet to be assigned to it. It is still evolving, which gives HEIs ample excuse to abuse it in the pursuit of lesser desirable goals of numbers, revenues or veiled ideological and hegemonic intents.

Distracted by forces such as massification and democratisation of education, internationalisation is “a way out” for those who have not considered how it would affect the ones on the receiving end.

The fact remains that many universities worldwide do not have a comprehensive internationalisation policy and framework that covers not only the academic part but also the socio-cultural dimension, core to any credible globalisation process.

Students and staff employee mobility schemes — which promote technical exchanges in a foreign university but ignore the value of the socio-cultural understanding and experiences —could can hardly qualify as “internationalisation.” efforts.

Currently, internationalisation is more of a “cherry-picking” exercise which is aimed at only some institutions and countries!

And for this reason alone, Haiti and others, which need help most, will remain outside of the internationalisation circle for a long while.

So the next time you come across the word “international” emblazoned on study brochures, take the time to read them carefully before you decide!

* The writer is the Vice-Chancellor of Universiti Sains Malaysia. He can be contacted at vc@usm.my

Learning Curve : Perspective

New Sunday Times - 02/07/2010

It is almost a cliché that higher education today must be internationalised if it were to be deemed as credible.

In fact, most institutions claim that they are internationalised, with permanent positions created to ensure that this actually happens.

Otherwise, they would be forced to do so by league table promoters who assign high points to such activities.

That is why we hear that some are hiring foreign faculty members to meet this aspiration because “internationalisation” often implies diversity of nationalities.

Even though there is a large number of local academics trained in diverse top-notched international environment and cultures, this is considered insufficient.

It is not surprising that meager resources are being channelled to meet such flimsy criteria, often at the expense of other priorities.

Some institutions claim to be the world’s most international institutes of higher learning (HEIs) or a global university to attract students. Never mind the quality of education, or whether it is truly international.

What is most puzzling is that these self-proclaimed HEIs are among the most well-advertised institutions, often supported by personalities less known in the academic world.

One would expect such institutions to be on every potential student’s lips and that the money spent on such promotional materials be put to better use.

It appears that being international comes at a price — assuming that this amount (and more) will be recovered through the number of students gullible enough to believe the assortment of fancy advertisements.

At one international meeting, I recall being asked if the Pacific International University in Malaysia is as good as it claims to be. Such is the power of advertisement, and until now I am still on the lookout for such an outfit in Malaysia!

But these are nothing new as universities increasingly behave like factories for the much sought after human capital. One of the tests for internationalisation had presented itself in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake on Jan 12.

Even before the tragedy, no university — no matter how international — had dreamed of setting up a branch campus, for example, on the beleaguered island. This is despite the fact that it is in the Western Hemisphere where most of the top international universities are located.

Not that the Haitians have no use for world-class international universities but rather the universities tertiary institutions have no use for the Haitians in the overall scheme of things. Instead, all are rushing to selected Asian countries — again sidelining the ones within Haiti’s league.

So much for internationalisation of higher education, which is beginning to sound more and more like commercialism.

Worst of all, we have yet to hear any big announcement of educational support — perhaps something similar to the Colombo Plan — from the rich and famous world-class universities!

Haiti’s hope to break free from its past lies in placing capacity building in any future plan to develop the island. This is crucial as Haiti has no tertiary institution of its own.

Could this be an opportunity for the likes of the Pacific International University to grab? We will just have to wait and see.

Even as the term “internationalisation” gains popularity, a firm meaning (of the word) has yet to be assigned to it. It is still evolving, which gives HEIs ample excuse to abuse it in the pursuit of lesser desirable goals of numbers, revenues or veiled ideological and hegemonic intents.

Distracted by forces such as massification and democratisation of education, internationalisation is “a way out” for those who have not considered how it would affect the ones on the receiving end.

The fact remains that many universities worldwide do not have a comprehensive internationalisation policy and framework that covers not only the academic part but also the socio-cultural dimension, core to any credible globalisation process.

Students and staff employee mobility schemes — which promote technical exchanges in a foreign university but ignore the value of the socio-cultural understanding and experiences —could can hardly qualify as “internationalisation.” efforts.

Currently, internationalisation is more of a “cherry-picking” exercise which is aimed at only some institutions and countries!

And for this reason alone, Haiti and others, which need help most, will remain outside of the internationalisation circle for a long while.

So the next time you come across the word “international” emblazoned on study brochures, take the time to read them carefully before you decide!

* The writer is the Vice-Chancellor of Universiti Sains Malaysia. He can be contacted at vc@usm.my