Higher education key to achieving MDG

Professor Tan Sri Dato' Dzulkifli Abd Razak

Learning Curve : Perspective

New Sunday Times - 05/02/2010

SOME 30 million children reportedly do not receive basic training in reading, writing and arithmetic in Commonwealth countries.

New Zealand, for example, is at one end of the scale with 80 per cent of its student population in higher education, while Sierra Leone is at the other extreme, with a mere two per cent.

The role of higher education in meeting the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) is a priority, says Commonwealth Secretary-General Kamalesh Sharma.

He was speaking at the recent Vice Chancellors Conference with a focus on Universities and the MDG organised by the Association of Commonwealth Universities (ACU) in Cape Town, South Africa last week.

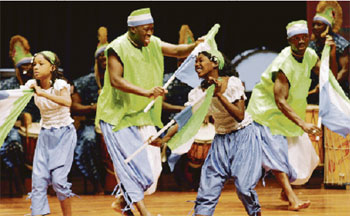

Sierra Leone youth performing a cultural dance at the Fully

Residential Schools’ Orchestra final competition in 2006 in

Kuala Lumpur. Only two per cent of the country’s young

people are studying in higher education institutions

The MDG, which was declared in 2000, comes to an end in 2015. The ACU initiative is timely as for too long universities have not been visible in working out solutions for such a vital global agenda. They prefer to remain strictly academic, if not insular.

The MDG, the first attempt at a globally embraced framework and goals for righting the wrongs of a world, should be worthy of support by all sectors.

Kamalesh says: "We are neither living in ivory towers nor tourists in search of ivory, lost in the metaphorical clouds swirling around Table Mountain; no, we are grappling with a real issue where our own wisdom is not necessarily accepted."

Other participants talked about the lost opportunities of about a decade now, and of the failure of universities to raise the voices of the poor.

It is as though learning institutions have not given much thought to the MDG.

Many seem to be caught in self-serving. This leads to what Professor David Hulme of Manchester University in the United Kingdom termed as the "world's biggest promises and lies".

The former is about good and noble intentions among the affluent such as promised by the Group of Eight (G8), while the latter refers to the stark failure to deliver.

A case in point is the 2007 London G8 pledge to spend US$60 billion (RM192 billion) -- dismissed as a smokescreen for the West's broken promises to the world's poor.

So it is no surprise that the implementation of the MDG has been rather weak, and most probably will not meet the desired targets in the next five years.

Insights into how MDGs are derived make it sceptical if the targets are intended to be achieved at all. After all they are very much framed by dominant parties mostly backed by Western powers. Some quarters are pressured by market-led persuasions regardless of the fact that countries such as Africa or developing countries in general may have a different focus and emphasis.

Still, universities cannot just walk away. The conference reminds them of their role in shaping future generations with new ideas and concepts.

The question then is can universities set new directions? Or do they merely respond to the demands of others, the market in particular.

Hulme asks: "Are universities institutional leaders or merely followers?"

He notes: "Eradicating poverty is not a technical question; those engaged with the project of ending poverty need to have political analyses and strategies that will promote the diffusion of an emerging international social norm -- the existence of extreme poverty in an affluent world is morally unacceptable."

Yet, most universities and academics involved in these processes "appear to have had only a limited understanding of ways in which knowledge creation fits into the political economy of poverty reduction".

In other words, there is still a long way to go. Unfortunately, when all is said and done; more is said than done.

Higher education institutions still need to demonstrate their development aims and credentials, and indeed apply them to achieving the MDGs.

And as Kamalesh correctly points out, universities are uniquely positioned between the communities and the governments they serve. They are at the core of societies -- and often in the rebuilding of broken ones as reflected by the MDGs. Unless this is done well, universities may be regarded as irrelevant.

* The writer is the Vice-Chancellor of Universiti Sains Malaysia. He can be contacted at vc@usm.my

Learning Curve : Perspective

New Sunday Times - 05/02/2010

SOME 30 million children reportedly do not receive basic training in reading, writing and arithmetic in Commonwealth countries.

New Zealand, for example, is at one end of the scale with 80 per cent of its student population in higher education, while Sierra Leone is at the other extreme, with a mere two per cent.

The role of higher education in meeting the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) is a priority, says Commonwealth Secretary-General Kamalesh Sharma.

He was speaking at the recent Vice Chancellors Conference with a focus on Universities and the MDG organised by the Association of Commonwealth Universities (ACU) in Cape Town, South Africa last week.

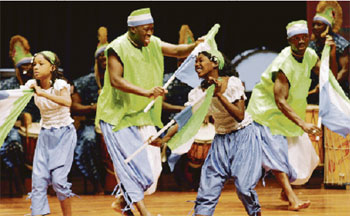

Sierra Leone youth performing a cultural dance at the Fully

Residential Schools’ Orchestra final competition in 2006 in

Kuala Lumpur. Only two per cent of the country’s young

people are studying in higher education institutions

The MDG, which was declared in 2000, comes to an end in 2015. The ACU initiative is timely as for too long universities have not been visible in working out solutions for such a vital global agenda. They prefer to remain strictly academic, if not insular.

The MDG, the first attempt at a globally embraced framework and goals for righting the wrongs of a world, should be worthy of support by all sectors.

Kamalesh says: "We are neither living in ivory towers nor tourists in search of ivory, lost in the metaphorical clouds swirling around Table Mountain; no, we are grappling with a real issue where our own wisdom is not necessarily accepted."

Other participants talked about the lost opportunities of about a decade now, and of the failure of universities to raise the voices of the poor.

It is as though learning institutions have not given much thought to the MDG.

Many seem to be caught in self-serving. This leads to what Professor David Hulme of Manchester University in the United Kingdom termed as the "world's biggest promises and lies".

The former is about good and noble intentions among the affluent such as promised by the Group of Eight (G8), while the latter refers to the stark failure to deliver.

A case in point is the 2007 London G8 pledge to spend US$60 billion (RM192 billion) -- dismissed as a smokescreen for the West's broken promises to the world's poor.

So it is no surprise that the implementation of the MDG has been rather weak, and most probably will not meet the desired targets in the next five years.

Insights into how MDGs are derived make it sceptical if the targets are intended to be achieved at all. After all they are very much framed by dominant parties mostly backed by Western powers. Some quarters are pressured by market-led persuasions regardless of the fact that countries such as Africa or developing countries in general may have a different focus and emphasis.

Still, universities cannot just walk away. The conference reminds them of their role in shaping future generations with new ideas and concepts.

The question then is can universities set new directions? Or do they merely respond to the demands of others, the market in particular.

Hulme asks: "Are universities institutional leaders or merely followers?"

He notes: "Eradicating poverty is not a technical question; those engaged with the project of ending poverty need to have political analyses and strategies that will promote the diffusion of an emerging international social norm -- the existence of extreme poverty in an affluent world is morally unacceptable."

Yet, most universities and academics involved in these processes "appear to have had only a limited understanding of ways in which knowledge creation fits into the political economy of poverty reduction".

In other words, there is still a long way to go. Unfortunately, when all is said and done; more is said than done.

Higher education institutions still need to demonstrate their development aims and credentials, and indeed apply them to achieving the MDGs.

And as Kamalesh correctly points out, universities are uniquely positioned between the communities and the governments they serve. They are at the core of societies -- and often in the rebuilding of broken ones as reflected by the MDGs. Unless this is done well, universities may be regarded as irrelevant.

* The writer is the Vice-Chancellor of Universiti Sains Malaysia. He can be contacted at vc@usm.my